![]()

There’s been some talk about the way I look in comments this week, which always brings up issues for me. Then I received the following email this morning, and I thought it was the perfect way to address this issue — which is not just a personal one, but very closely tied to fat acceptance and feminism.

Dear Fat Nutritionist,

Here’s a question from a first-time visiting guy: how would you rate your awareness that you’re so beautiful it’s kind of totally ridiculous? You know, on a scale from 1 for “totally oblivious” to 10 for “painfully aware, I get messages like this every day.”

Have an awesome week … and good luck with the site!

-Anon

Hey Anon,

I appreciate the compliment, and it’s charmingly stated. You probably intended it as a rhetorical question, but if you’ll indulge me, I’d like to tell you a story about my awareness of my own beauty.

When I was very little, I became aware that I was considered more valuable to other people when I looked a certain way. On days when my mother curled my hair and dressed me in ruffles, I was treated with a kind of fawning admiration by the adults I encountered. When she didn’t, and as I grew older, out of that perfectly sweet toddler age and into a considerably more awkward and willful one, the more invisible I seemed to become.

I proceeded through childhood seeing romantic movies, even cartoons, that depicted the lives and problems of conventionally beautiful people as more important, and endlessly more fascinating, than the lives and problems of the dowdy or traditionally unattractive.

Do you remember how, in ancient times, and even up through the past several hundred years, plays and novels and epics almost exclusively concerned themselves with the lives of royalty, the nobility, or, at least, the very, very wealthy? And have you noticed that now, in this supposedly classless modern society of ours, the stories of the rich and powerful have simply been exchanged for the stories of the young and beautiful? In 1847, Jane Eyre was considered a startling departure from this convention — and it kinda still is. I’m sure you’ve noticed. At any rate, from a very young age, I did.

I spent my girlhood, like many American girlhoods are spent, wishing fervently to become beautiful. When I was ridiculed in school, when I was ignored or picked on or called a nerd, I turned to the fantasy of sudden beauty as some kind of protector-saint, as though it could save me from the pain of being a human among other humans. Unfortunately (I thought) for me, I was an awkward kid, a tomboy with straight brown hair and glasses, and a pearish figure unaccommodated by the fashionable clothes of the day.

I began to seek beauty like a person possessed, starting around age 11. I read fashion magazines and bought makeup. I put the makeup on. I looked ridiculous, but I kept practicing. I bought clothes, and did it all wrong and got laughed at and made fun of, but I kept trying. I had a feeling that if I could just find the combination to this particular padlock, I would be liked by the right people, I would have the right sort of life, and I wouldn’t have to feel like an alien or an outcast anymore.

Once I hit puberty around 12, I basically looked like a grown-up and stayed that way. People thought I was an adult when I was still in gradeschool. Objectively, my looks did not actually change very much between the ages of 12 and 16.

So imagine my surprise when, one morning when I was 16, I got the combination right — the stupid padlock opened.

At that point, I’d actually sort of given up on the whole enterprise of becoming fashionable, and thought to myself, “Fuck it. I’m just going to do whatever I like.” Since I have a kind of eccentric personal style, this meant styling myself in a way that would have been right at home circa 1915. The previous evening, I’d bobbed my hair and received some new clothes in the mail. All the years of making myself look absurd with makeup had actually made me quite skilled with it.

I got dressed and went to school as usual — pleased with myself, but not expecting anyone else to give a rat’s ass. I walked into school where, just the previous day, I’d been ignored, completely invisible, and considered nerdy and unfashionable and weird. As the doors opened, the first thing I heard was, “SHE LOOKS LIKE A MODEL,” loudly stated by the most intimidating punk of the school to his entire group of intimidating friends.

I froze, half-mortified and half-transfixed. It was one of the few times I’d heard anyone comment positively on my appearance since I was a toddler. It was exactly what I’d been craving for so many years; how could I not feel at least partly pleased? But I was also taken aback — this was not, after all, what I was going after when I’d gotten dressed that morning. Still…it was not exactly a bad result, no? Surely my life would now get better?

Sadly, I realized too clearly that I was not, objectively, “beautiful.” I realized that beauty was not a static thing, not a fixed commodity, and that there were very few people in the world who rolled out of bed looking the cultural ideal. And I was certainly not one of them.

For me, beauty was a costume I put on in the morning and took off at night, when I was finally alone with myself. I knew this, and it made me nervous as all hell, frightened that someone would see through my disguise and take away the status I’d finally, accidentally, managed to achieve.

I began to feel an external obligation to put on my beauty costume, every single day. I was unbearably nervous to leave the house without it. Sometimes it took hours. Sometimes it meant getting up at 5am. Sometimes I rebelled — there was a period where I refused to wash my laundry, to do anything but lay in bed most of the day, and I would literally pick my clothes up off the floor and put them on, then tramp through the mud in my heeled oxfords and long skirts to school.

Pretty soon, I stopped leaving the house as much as possible.

There was another reason for this — when I reached puberty, but not quite fashionability, at age 12, I had my induction into the world of womanhood via the ritual hazing of sexual harassment. I was tormented, squeezed, hissed at, touched, groped, fondled, and pulled forcibly into people’s laps at school.

Do not misunderstand: this was not flirting. It was humiliation and cruelty. These people were not interested in me as a human being; they did not have crushes on me; they did not care for me. It was degradation, plain and simple. And I wanted no part of it. I physically and vociferously fought back. But I was confused — I did not understand why it happened, what I’d done to deserve it, and why no one came to my aid.

As bad as this was, it only got worse when I started dressing in beauty drag. I began attracting the attention of perfect strangers, of people much older than me, people who didn’t just mean to humiliate me, but who actually meant me harm. I went from feeling like an invisible person who was occasionally objectified for other people’s pleasure, to being a deer in hunting season. I was highly visible, something about me was now considered highly desirable, and I was no longer just vulnerable to attack — I was actively targeted because of the way I looked. My life and physical safety were threatened more than once.

My peers also seemed continually amazed to discover that I was intelligent, as though the previous ten years — when I’d been known by reputation as a school-nerd — were blotted out completely by my changed appearance.

Even so, boys at school wanted nothing to do with me — except to talk to their friends about how badly I needed to be screwed — and girls who weren’t already my friends started kissing up to me because my status was now higher. I rebuffed them. I told them off (in my head.) But I was desperately lonely.

As I mentioned, I started becoming afraid to leave the house. A computer nerd from way back, I started using IRC a lot in order to talk to people in a context where I could control how/when to reveal my sex and my appearance.

I had internet boyfriends, who sent me mix tapes, instead of real relationships because I thought I could keep myself safe that way. I was almost completely isolated.

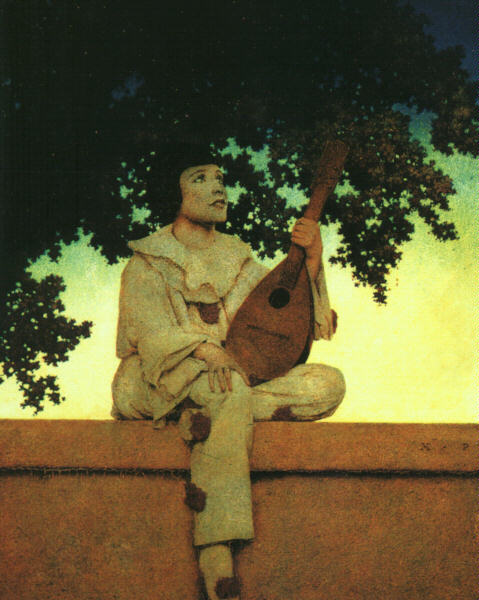

I’d been depressed since about age 12 (SHOCKER), but I was finally diagnosed with depression formally by a therapist who told me, “You look like a Maxfield Parrish painting.”

My last year of high school, I started to mess around with my beauty disguise. I played with the levels of visibility I could achieve, I suppose as some manner of taking back control over this thing that had gotten entirely out of hand. I dressed up some days, and then, other days, I’d wear running shoes, old jeans, my mom’s jacket and glasses.

Once, a kid I didn’t know approached me at school as I sat in my habitual spot in the commons, doing homework.

“Excuse me,” he said. “I have to ask — are you the same girl who normally sits here?”

“Yeah…?”

“I mean, you normally wear a long dress, right? And no glasses?”

“Yes.”

“You just — you look like a completely different girl. Wow. I thought you were someone else.” And he walked away, shaking his head a bit.

I was oddly pleased by this, but it also reinforced my knowledge that the beauty thing was just a disguise, a costume.

In college, when I was 18, I saw a boy in my mythology class who seemed interesting. He took absolutely no notice of me for several weeks, dressed in my jeans and army surplus jacket. I decided to conduct an experiment: for the next class, I would dress up and see what happened.

What happened was he came and sat by me, asked me if I was new in the class, then carried my books while walking me to my dad’s car when class was over. The only thing different was my mode of dress.

I am older now and a lot fatter, but I still can manage to put on the costume when I need to. I am conscious that I am treated differently when wearing beauty: better in certain circumstances, worse in others. I am sexually harassed more on the street, but receive better service and kinder attentions from people. I get more attention, but people, perhaps, take me less seriously.

I made the conscious decision, when I started this website, that I would use an attractive picture of myself on the front page. Because being fat in this world is already a black mark against me, I knew I would have to tap some of the status that my false beauty can afford to partially make up for that. I knew my writing would be more likely to be read, and people would be more interested in hearing me out, perhaps even giving me media coverage, if they thought I were beautiful.

The truth is the same as it has always been: I’m not actually beautiful. I’m simply and idiosyncratically myself. Beauty is a cultural construct designed to keep people balanced on a knife-edge of anxiety over the potential loss of status, and the rabid desire to gain it. That knife-edge is so slender that hardly anyone, as I said before, rolls out of bed in the morning and balances on it effortlessly. Those who do are highly paid to do just that.

There will come a time when this costume no longer fits, when I am old enough and changed enough that no amount of makeup, no hairstyle, no set of clothes will be able to obscure my nature to the extent necessary to imitate cultural standards of beauty. When that happens, I imagine I will grieve, but I will also feel relief.

So, to answer your original question, the answer is somewhere around 152. Not because I’m constantly showered in praise for my looks, but because I deliberately construct or deconstruct this papier-mâché facade in front of my mirror, depending on what needs to get done that day.

Oh, and I married the internet boyfriend who sent me the most mix tapes.

Warmly,

Michelle

P.S. I hope you don’t mind, but I’m publishing this email :)

Comments

85 responses to “Dear Fat Nutritionist – You’re pretty good looking (for a girl.)”

Wow, awesome post/letter. So much of that is so familiar (although I was always fat and picked on more for that than any transformation I could manage). The part about unwanted attention – verbal and physical – strikes memories, in particular. Why did no one help?

Once. Again. Blown Away.

Another amazing post. I too am someone who has found the attention I have gotten because of my conventional prettiness overwhelming and confusing most of the time. I am sure some of my ED history and my weight gain has been because of my unconscious need to “hide”. I love the term “Beauty drag” and have never heard it before – and it is SO true! So now I have a term for what I do on the days that I feel up to the “special” attention – I put on my drag :)

I also appreciate your willingness to discuss your beauty; this can be hard to do because of fears of sounding conceited. Thank you so much.

I also appreciate your willingness to discuss your beauty; this can be hard to do because of fears of sounding conceited.

Oh, totally. And how ironic is that, by the way? I mean, I wasn’t the one who started calling myself beautiful — THEY were. Quite loudly and repeatedly and insistently. So, what, like I’m not allowed to be aware of that and talk about it?

I mentioned this in the past on my old blog, but I’m very disturbed by accusations of vanity and conceitedness that are often thrown at conventionally attractive women. I think it’s a form of shaming — basically saying, “You can only be physically attractive for the benefit of other people. You’re not allowed to notice, or enjoy, it for yourself.”

I call shenanigans on that. It’s bollocks.

This can actually explain the insecurities of some who are conventionally attractive. I’ve known people who I’d consider stunning beauties that didn’t feel they were that pretty.

“I spent my girlhood, like many American girlhoods are spent, wishing fervently to become beautiful”

So, so many things in this that I identify with. The padlock (I’ve never figured out how to open mine), the “Beauty Disguise”, being seen as an entirely different person due to style of dress…

I wish I could say something more coherent and meaningful, but by god do I understand this.

I agree, Mina. I was never able to open that padlock either and spent most of my childhood (and, I suppose, the better part of my adulthood to date) wishing that I could.

I’m guessing no one helped because sexual harrassment in schools is lumped under the “horny teenager” umbrella, and no-one wants to deal with it. I was sitting in math class in 8th grade when the boy behind me reached around and cupped my breast. I let out a blood-curdling shriek and slapped him. He literally told me, “You’re beautiful when you’re angry.” I ran out of the room.

The guidance counselor basically told me to calm down. Nothing happened to the boy. They wouldn’t even let me change seats.

No other child came to my aid, because what the hell were they going to do?

…yeah.

In my case, the teacher who witnessed my harassment literally looked terrified. I knew she knew it was happening, but she was just as afraid of those boys as I was. And they were 12, for f’s sake.

That is seriously fucked.

Reading the original post and these comments make me realise how lucky I was. I went to a school where very little was done about bullying, but I was also strongly favoured by the teachers and was very strong physically. I remember a boy running past and grabbing my breast, and I immediately grabbed his hand so he couldn’t run away, and punched him as hard as I could in the back. The other girls were sexually harassed, but the boys kept away from me.

But now that you mention it, I do recall girls being told to “Calm down.” It just wasn’t an issue for me. I am so stupidly lucky. I’m not saying this to be like “Eh, you could have avoided that shit VICTIM BLAME.” but more I was just lucky I established such a reputation early.

I know that isn’t “supposed” to sound like victim blaming, but it sort of sounds like it was. I too, was physically strong, I hit my attackers, my teachers loved me, but no one stopped the boys from harassing me. It was an example of rape culture.

I did have a male history teacher let me eat lunch in his room every day. At great personal risk to himself, letting a female student be one on one with him like that. He protected me in his class too, but that was one period a day, and one lunch.

If adults were not going to step up there was nothing more I could do to defend myself. And maybe the boys stopped TOUCHING you but I doubt that was the last of the harassment from them. I am sure there were comments and jokes and things that you were unaware of or didn’t know about. Your friends or classmates probably heard it all though. And those comments and jokes and jabs are all also part and parcel of rape culture, they teach the other girls to be afraid.

great post, michelle. thank you.

This is so excellent, and I think you’re going to get tons of comments from people who relate to it.

Well, you DO look remarkably like Betty Page, in my opinion, and she is of course a famous face for beauty from early last century. I totally understand where you are coming from with seeing beauty as a costume. I, too, went through many years of invisibility and awkwardly seeking that perfect fashion persona that might break me through into something noticeable and attractive. And, I too, felt a bit intimidated by the attention when I finally found that magic look. I admit, in my case, I was saddened by the fact that the “magic look” for me involved a great deal of slutty dressing, and for the most part I’ve given up dressing for “beauty”. I’m so lucky that my fiance thinks I’m beautiful in baggy sweats and ragged T-shirts! When I do take the time, occasionally, to put on my beauty costume, it never feels quite right, and is usually more draining on me than it’s worth.

It’s the bangs, truly. Without them, there’s no resemblance. (And, for what it’s worth, that picture is now two or three years old. My hair is slightly different.)

I’m also lucky to be with someone who doesn’t seem to notice the change in my appearance when I go from beauty drag to shitty old pajamas. And I like the fact that he doesn’t compliment me very much (an occasional, “You look nice” as reassurance when I’m fussing in the mirror — I prefer “You smell nice” because I love love love my perfume) just as he never makes comments about me looking dowdy when I do.

I like the fact that, to him, I’m the same Michelle, no matter what I’m wearing or how I’m presenting myself. He sees what I actually look like, consistently, and isn’t fooled by the surface changes.

You know, he could consider the transformations hot. Just as you choose different “disguises”, he enjoys each one differently. Getting to know you online first helped him see who you really were and I’m sure he learned a lot of those things that irk you so figured out what to say and how to say it so that his comments mean something and aren’t compared to the harrassment you’ve experienced.

PS. I’d still like to meet up sometime when you are in Chicago next.

This post is amazing. This bit in particular grabbed me:

Do you remember how, in ancient times, and even up through the past several hundred years, plays and novels and epics almost exclusively concerned themselves with the lives of royalty, the nobility, or, at least, the very, very wealthy? And have you noticed that now, in this supposedly classless modern society of ours, the stories of the rich and powerful have simply been exchanged for the stories of the young and beautiful?

I remember reading in one of my music textbooks about the change from operas about gods and royalty to more realistic opera–stuff like Boheme and Carmen that’s about regular people, and how that mirrored a shift to a more democratic society in the Western world.

BUT! You are so right! I can’t think of a single verismo opera that isn’t about gorgeous young people. It’s like, “Sure we can tell stories about the working class, but they’d better be nice to look at.” So interesting and thank you for sharing the thought!

There will come a time when this costume no longer fits, when I am old enough and changed enough that no amount of makeup, no hairstyle, no set of clothes will be able to obscure my nature to the extent necessary to imitate cultural standards of beauty. When that happens, I imagine I will grieve, but I will also feel relief.

This really resonated. Other than being fat, I have always hit mainstream beauty standards dead on – in other words, by the dominant definition, I have always been very pretty (posting under an assumed name, too). After I hit my mid-20s, I looked much younger than I was with very little intervention on my part. I’m almost 40 now, and I’m finally starting to slip out of those standards. It’s subtle, but there. Getting a little jowly, a lot gray, my body shape is changing from more of an hourglass to more of droopy apple. Sometimes I get very grasping about it, panicking that I’m losing my pretty privilege. Other times I’m thrilled – finally I can wear whatever the hell I want without somebody asking me why I’m hiding my face/hair/eyes or without hearing the, “she’s so pretty, too bad she’s fat” comments.

I can’t relate to being beautiful or being able to don “beauty drag” – but I think I know what you mean. I have a few friends who I think fit in this category. Thank you for your writing; it’s definitely a great subject you’ve handled in an interesting manner.

I went most of my life being praised, praised, praised for being “smart”, and that has its negatives too… this beauty essay kind of reminded me of some of it.

Yes. I have very similar issues with the whole “intelligence” thing. To the point where school now induces panic in me (because omg what if someone finds out I’m not actually all that smart??? My entire sense of self-worth will crumble.) Different post for a different day, though.

This really resonates with me. I was always the smart kid – the only girl in advanced math in elementary, one of the few girls to take sciences a year early, went to a top ranked college, and currently a graduate student at…ok, this sounds like bragging. Point being, I’m constantly afraid that I’m going to be “found out;” that I don’t deserve the grades I make, or shouldn’t have gotten in in the first place. It’s weird.

I think being smart insulated me from having to be pretty, though. I built my identity around my intelligence and never expected to be attractive. Of course I wanted it, but I just didn’t think it was a reasonable desire. I still find it surprising that, despite developing young (I also looked more or less adult by high school), I actually never got much harassment. None in school, that I can remember, and nothing physical outside of school (just honks and revving car engines). Who knows…

Yeah, okay, how messed up is THIS? I actually don’t believe that I deserve good grades unless I manage to achieve them without studying. Like, for tests and things. Not only does the prospect of studying for tests cause paralyzing anxiety for me, it also kind of feels like cheating.

Because, apparently, I believe that I should just KNOW EVERYTHING IN THE WORLD.

/neurotic

That was actually a serious problem for me. I never had to study when I was younger, so I never learned how. I think that’s a large part of the reason I feel so undeserving…

Yep. Same here. Never studied in high school, really. Guess I still feel like I shouldn’t have to. Or maybe even…I’m not supposed to?

But, you know, chemistry doesn’t come so naturally, it turns out!

Hahaha…chemistry was the one class in high school I really struggled with. First time I ever saw a tutor.

hint, hint– everybody in grad school feels like a fraud!

It went away for a few months after I passed my comps, came back after I started in earnest working out the mechanics of the dissertation…

Also, me too folks– I didn’t study through my first M.A.– the Phd program has required it…

Back to grading :)

I realize this is about a month late, but this is what you guys are talking about is called Imposter Syndrome.

I had the same problems too. Apparently it’s really common.

I really hope you write that post, because I’m in the same boat, and have trouble seeing a way out. Being smart has been the main pillar of my self-esteem since – before I remember, actually.

You know how much therapy I’m gonna have to do before I can write that post??? :)

SO funny. Studying feels like cheating to me too. Terrible.

Great post, Michelle. I really identified. Fantastic work.

FYI- You look nothing like Betty Page, but I have always thought of you as particularly beautiful.

This is such a great post. It’s rare that I get to hear these sort of inner thoughts with such honesty. Thankyou for sharing.

Thank you for sharing this. It’s important, and it’s so hard to talk about…I think an awful lot of people grow up thinking nobody else gets caught in the same trap or feels the same way about it.

Great post. I found this REALLY helpful today, and very much related to a lot of it (as usual) in a gay-feminist-man-with-an-ED kind of way. I was also JUST trying to explain the concept of performing beauty to my partner a few days ago (I am kind of beating him over the head with 101 stuff at the moment to bring him up to speed), and now I have something written that explains it twenty times more clearly than I could. I’m so glad you’ve added the Fat-O-Sphere feed to your page, because now I have an excuse to check multiple times daily! Thank you.

Awesome! Good luck with your 101-ing. I know that can be tough.

Great post. I totally wish I were beautiful, even with a case of Teh DeathFatz, because beauty does make a difference in how one is approached by others. It’s all degrees of crapness, but what can you do except deal with it the best way you can?

However, some people – and until I see a different pic of you I’ll take you to be one of them – will always look good no matter what they wear.

When discussing the “obesity epidemic” on the internet I come across a lot of people that seem to have a very particular idea of what fat is, I often get the feeling that in their minds prettiness might somehow mean “less fat (less like the symbol of fatness)” than someone of the same size. I don’t know if I’m explaining myself properly but I wonder if there is some cognitive dissonance for some people when they see your picture.

Yes, I think you’re right, and sometimes I wonder that myself — if people are dismissing my fatness based on their perception of my prettiness. I definitely wondered that at work, sometimes.

I mean, I am visibly quite fat. My BMI is over 40, so I’m well into morbidly obese territory. But I know that I am sometimes treated differently — for example, when people can see my face clearly vs. not. I am far more likely to be harassed for being fat (like have people shout FAT BITCH at me from cars) when they cannot see my face.

Firstly, I adore this post sooo much, even though I don’t think I ever unlocked the mystery box of beauty except in the case of my husband, who likes the look of me.

Secondly, I have to admit, because of your photo, I’d always imagined you as another inbetweenie, as there seem to be many of them blogging, especially young, white, conventionally pretty inbetweenies. That’s the acceptable face of fatness, still, and it often makes me sad.

Thirdly, because I’m feeling enumerative today, I’ve often felt that sense of beauty as performance rather than fact, but my problem with it is that I am a feminist who believes, quite strongly, that performing that act as a personal choice is also a political one as well. You hit on the edge of that when you wrote, “Beauty is a cultural construct designed to keep people balanced on a knife-edge of anxiety over the potential loss of status, and the rabid desire to gain it.”

When one of us puts on the face and goes out, we gain privilege from it at the expense of anyone who doesn’t. We are more likely to get hired for a job over someone who doesn’t wear makeup, for instance.

So… based on what you wrote, I’m wondering where you stand on the notion that we are all part of constructing the cultural construct. That is to say, if we’re balanced on that knife-edge, how do we put each other there?

In terms of what you wrote, and in terms of solutions, I wonder what would happen if, instead of having that single picture of you glammed up and looking like you do there, you had two photos–both you–both human. Would that help to blunt the knife edge that you mention, just a little bit, for women who, like me (and, I suspect others) look at that photo and feel the knife cutting the soles of our feet even as your words promise a softer landing?

young, white, conventionally pretty inbetweenies. That’s the acceptable face of fatness, still, and it often makes me sad.

This is very true, and it makes me sad as well.

As far as the pictures go, I was actually thinking about that myself this morning. But it’s also really difficult, in a personal sense — being able to put on that “mask” is not just a privilege-gaining move on my part, but, in a way, a “hiding” move as well. I don’t actually want people to see what I look like, because it is something I take a lot of care to hide most of the time, even from those people who see me in person and not just in pictures. Because, like most other women, I imagine, I am insecure about it.

But it’s definitely something to keep thinking about.

Although…on second thought, you convinced me. Here’s a not-terribly-flattering picture of myself with my hair grown out, wearing glasses, probably not wearing much, if any, makeup. It is also a couple of years old, so I can deal with it better than if I saw a more recent one (also, my hair is quite different and I no longer wear glasses, so it doesn’t exactly represent me as I am now, but it gives you the general impression of my natural state.)

Ok, I know this is not the proper response, but I have to be honest – you look pretty there, too , as far as I can tell.

I guess it’s not just actual appearance, but the signals (makeup, clothes) that scream “I’m beautiful! I’m sexy!” influencing the way one is treated by total strangers, though.

I’m sure there are many more unflattering pictures of me floating around. But that’s about as far as I’m willing to go, at this point! I do, after all, have body image issues and insecurities about my looks just like most other people here.

I think you have a really genuine and kind smile, which also comes across in your writing :-)

I love this post. I showed some passages to my husband (the ones about the fantasy of beauty as a protector-saint and feeling like a deer in hunting season) because they described my experiences so well. When I’ve been “thin” (actually “average”, but that’s my thin), had long hair, etc. I was a target; gaining 50 lbs or shaving my head (as I did at age 18) turns me invisible. Neither state is all that comfortable, and I”ve often wished I could exist in the “middle ground” most men seem to enjoy – seen neither as a sex object nor an asexual being – but the perception of “beauty” seems more like a light switch than a continuum.

Yeah, at my thinnest I passed for average, but my BMI was always in the “overweight” range, even as a teenager.

Elsewhere online, someone described being treated like an “attractive nuisance” (the legal definition) because she was a woman. I have never before or since seen that feeling so perfectly stated, and I’ll always remember it.

Wow.

There is so much good stuff in this and the comments. Deep stuff.

I think about beauty way too much, I would love to write about my history with it, as you have. And I am fascinated by how others perceive themselves compared to how I perceive them.

Just yesterday, I was processing this thought: “I feel intimidated around people — especially women — who are good looking and stylishly dressed.” and I immediately imagined my therapist saying something along the lines of “imagine how others must feel around you, then.” I imagine that I don’t come across as put together, good looking or intelligent. Kind or sweet, maybe. Once I start talking, I imagine that I deconstruct what other people think of me, and surprise them. I know that happens when I dance — I surprise people with a freedom, lightness and bounce they aren’t anticipating. So, if what I’m perceiving is real, that my appearance is underwhelming if not offputting, then there can be this little “gift of surprise” — certainly double-edged.

I longed for a key to the paddlock, and felt that I would never obtain it.

Nowadays, I define beauty as that spark of interest, what makes someone intriguing to me. I really am intrigued by a broad number of things, but the main one for me seems to be a lack of artifice — an openness to the human experience. Ironically enough, people who are “good looking and stylishly dressed” might initially be offputting to me until and unless I can get that “wink” about the “beauty drag.”

Mostly, these days, I’m surprised when I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror and see someone who meets my own definition of beauty. Poised between youth and oldness, I see a soulfulness in my eyes and graying hair that I find appealing. I have zero trust that what I see is what most others see, but strive to I care less and less about “others” and more about those who are open enough to see what unfolds as they come to know me. I strive to also be open enough to see what unfolds as I come to know other people, including the “good looking and stylishly dressed.”

You know what Michelle? I think you’re beautiful, for what it’s worth. And not because of your (very nice) picture up there. What I find beautiful is your honesty, your courage, your sense of humour, your willingness to show your cards from time to time, your intelligence, your thoughtfulness. I thought you a beautiful woman some time ago.

Seconded! And, great post. It clearly expresses a lot of things that been peripherally aware of, but hadn’t fully analyzed.

Snap! Me too!

I got some unwanted attention as a kid, as well. Boobs squeezed by strangers, much older men aggressively trying to get with me, doctors (!) who gave me a hard time because I wouldn’t sit on their lap. I conciously tried to be invisible, which wasn’t hard as I got chubbier. Now as I’m getting to that age, it’s getting easier again, and I don’t tend to attract much attention unless I dress nicely, which I don’t. I am struggling a bit, with becoming “conventionally attractive” (aka thin enough to be acceptable), just as I’m getting old enough to be out of the running.

I, too, think you’re beautiful, and have a bit of a girl-crush on you. The way you open yourself up in these posts blows my mind. Hopefully you’re not offended, and won’t use my comment in a future post about annoying readers.

Well shit, there goes tomorrow’s post :)

Michelle,

You could be telling my own story. The quest for that elusive thing named “beauty” obsessed me for most of my life. At 42, I still find myself wondering if I would be more successful in my chosen career (I’m a writer) if I looked better in photographs. I love your contention that beauty is a ‘costume’; I’d never considered it in quite that light before. I always felt that I had an obligation to look a certain way, i.e., like the women on magazine covers.

At 42, I am rapidly approaching the age when I can readily assume a delicious invisibility – by going without makeup, wearing my ‘comfortable’ clothes, and so forth. For an author, such invisibility confers a wonderful ability to observe the world around me, and I find myself grateful to be part of the background.

Thanks so much for this wonderful post.

Wow. This sounds kinda familiar. When I was a little girl, I remember being thought of as cute, the cutest of my sisters. I don’t really remember how I knew that, I think my sisters said so.

I think I was expected to grow up very pretty, and I kind of did, except for the super fatz and whatnot. I think inside I feel that my family is disappointed in me for not dramatically losing weight like my mom did in high school.

I also get the not studying thing, I totally bombed in high school, and now I’m getting good grades in college, and I feel like I kind of don’t deserve them.

What a mess.

Honey,

You were always beautiful, from the moment they put you in my arms on your birthday right through the days of the curls and lacy dresses with matching hats (sorry ’bout all those but I couldn’t resist). From those early years to the years of Dr. Martin boots and the all black wardrobe including dyed black hair, you only became more beautiful to me. Now, as an adult woman finding her way in the world and definitely making her mark on it, you are even more beautiful….. with or without your “beauty drag”. Oh, and the internet boyfriend who sent all the mix tapes…he turned out to be one in a million!

Awwww :)

Thanks, Mom.

And I can’t wait to see the whole beautiful you and your handsome husband in a couple weeks!!

Afuckingmen.

Beauty is confusing. I’ve always wanted to be typically attractive without any of the artifice. [Although, writing this down, I realize how this is so completely impossible. Like, “I’ve always wanted to be a mermaid but without having to live underwater.”]

During college, I was regarded as beautiful. However, I found out that that designation will get you better treatment but less respect . I got more attention from people, specifically men. Flattering comments and suggestive offers were made regularly. But I was rarely ever respected. My space, my opinions, my personality no longer existed. When these fundamental aspects of my being finally penetrated the other person’s idea of me, they always acted shocked. I remember being told by two different boyfriends, “I’m just surprised that you’re as smart as me.” [In my mind, I’d say ” ‘AS smart AS?’ Don’t you mean SMARTER THAN, dipshit?” But, because I am a dignified person, I’d just smile serenely and let them stumble on their idiocy.]

This experience of being objectified and harassed also turned me into a hermit in college. I couldn’t really talk about it with anyone because it’s not a problem people want to hear about. (It’s certainly not one I would have wanted to hear about before I had this experience.) I guess beauty really is like wealth and fame — you’d think these qualities would get you a happier, more fulfilling life, but they don’t. They just isolate you from other people, alienate you from yourself, and bar you from experiencing true intimacy, respect, and self-empowerment.

Now I am no longer regarded as beautiful, and it’s mostly a relief, but I still sometimes pine for it. I miss being attractive, being visible. However, I don’t miss the ridiculous assumptions, the harassment. I forget, over and over, that it’s a package deal, that with the attention comes the objectification. But I remind myself. I know.

N – I’ve always wanted to be beautiful without any of the artifice, too – and it works(ed), to a point. See, part of what the beauty drag does is make you think you’re beautiful. If you think you’re beautiful without it, then it does do something for you. Could be confidence, happiness, good posture, friendliness; whatever.

Hey Deeleigh,

That’s an interesting point. I imagine if you can translate that feeling of beauty while wearing beauty drag out into your puffy-faced-wearing-pjs-eating-cereal moments, then it is quite a useful tool. When I was a teenager, though, I’d usually shriek to my mom “You only like me when I’m wearing maaaakkkeee uppppp!” I created a dichotomy in my head that beauty drag is false me and sweatpants-wearing is real me. Now I realize that beauty drag is for alot of people their realest self, their truest, most creative self-expression. And sweatpants-wearing me doesn’t feel like real me, it feels like sloppy me… I guess I’m still figuring this one out.

What has made me feel insanely beautiful is honest, supportive friendships (I’m not dating anyone right now). Damn, I feel so much better — safer, happier, more connected and more beautiful — when I feel like there’s someone out in the world who knows and accepts my true thoughts and feelings. I wonder if this is a common experience, that having positive close relationships makes people feel more at ease in their body and/or beauty?

Oh, I’m positive that you’re right about that. I think that strong and supportive family and social relationships are incredibly important to human beings, and that they do all sorts of things to make us happier, healthier, and more attractive. That’s part of the reason that the shunning, blaming, and shaming of fat people is so dangerous. It can turn “fat people are unhealthy and unhappy” into a self-fulfilling prophesy.

Yes, I definitely think having a supportive relationship (with my husband) started me along in a significant way toward accepting my body, even though I was far from discovering fat acceptance at that point.

I thought, all the while I was experiencing the dysphoria of the “beauty drag” I’d discovered, that my body was one of the terrible secrets I was hiding underneath my choice of clothing, by distracting people with my made-up face, etc. I was sincerely convinced that the first person to see me naked would run out of the room, screaming at my hideousness. I am not exaggerating.

What a wonderful surprise then, that that didn’t happen. And, in fact, I managed to have a dialogue with my husband about my hips (my most hated body part) one of the first times we were together. After seeing them from his perspective, I realized how skewed my view of my body was, and that maybe, just maybe, I was lovable as I was, at least to someone.

Humans are creatures so dependent on social approval and, dare I say it, love, that this kind of acceptance from someone else can’t help but have a huge impact on us, though perhaps in some ideal world, we’d come to self-acceptance all on our own.

“I’ve always wanted to be a mermaid but without having to live underwater.” ha ha ha ha … I identify with that. As a kid I was so ashamed of wanting to be really beautiful because a truly nice person wouldn’t think of trivial things like that. What a crock. Then at 14 I went through a “pretty” phase and I was totally freaked out by the unwanted attention, and more so, by my craving for more, more, more and my lack of defenses.

Holy fucking crap. I’m sitting here at work trying not to cry – this brought up a bunch of stuff for me, and oddly, clarified a lot of things that needed clarification.

Now I have thinky thoughts for the weekend. Thanks. :)

Your childhood is remarkably similar to mine. I got harassed for being gay despite not being fully aware of it myself until I got to college. Being 30 now, I am much more confident and more often than not really don’t care what others think of me. I care more about the one’s whose opinions matter in general to me. I was curious about the mix tapes, I’m glad to see you snagged a good one. :) I’m sure I dealt with depression from 6th grade on although it wasn’t diagnosed. I do believe that a big part of the change you noticed that one day at school when you recieved the comment about being a model is your confidence. You had decided at that point to not care what others thought. You were happy with who you were and you had figured out how to express that properly. People who know me now don’t beleive that I was such an unpopular kid. I couldn’t be paid enough to relive those years unless I could go back knowing what I know now.

Hey, we’re the same age :)

It’s interesting how kids can so easily single out other kids who are somehow, inexplicably, different from the others. The big thing about me was that, at some point, most kids felt the need to tell me I was “weird.” I suppose it was because I was a fanciful (and somewhat silly) kid. It bothered me a lot then — now I am much more comfortable with my eccentricity.

Yeah, but it’s us weirdos that turned out happy and healthy, Michelle!

There were some real jerk-offs in our universe. I don’t know what their issues were (I am sure there were many), but I think those labels helped me, somehow.

Every time someone said something mean to me, it made me angry and that anger turned into a whole bunch of internal power and positivity. I am so thankful that I was different and I had a support system that encouraged me to stay that way.

omg someone who knew me in highschool!

How the heck are you, Emilie?

And, yes, weirdos FTW

This was a really great post.

I am one of those people who is awareness level 0 on most things. Serious case of obliviousness, so I’m always wondering about how other people perceive me. Reading a lot about fat acceptance, thin privilege, beauty ideals and feminism has made me try to be actively aware of how people treat me, even if I feel like I’m almost trying to back into how the world perceives me that way.

I don’t think I’ve ever figured out the padlock. On one hand, I want to be seen as beautiful, but on the other hand I’m very much a tomboy and feel like makeup, clothes, etc are 1) things I am not very good at and 2) wastes of time. I think the latter is something were conditioned to believe. We have to look x way, but the energy devoted to it is wasted energy, spending time on silly things.

I actually have a pretty strong streak of tomboyishness in me, and have for a long time, but I started to admire high-femme stuff when I was around 10 — mainly due to my fascination with anything “old-fashioned.” I have a really strong aesthetic ideal, I think coming from a visual artistic streak in my family (my dad’s a mechanic, but also a painter and incredibly talented illustrator and calligrapher and photographer) and I enjoy putting on the costume nowadays, because it doesn’t really feel like a burden.

I love makeup. I love clothes (for a while there, I wanted to go into fashion design, and I taught myself how to sew, and I took a tailoring course.) But I don’t read any women’s magazines, or fashion magazines, because they’re often so misogynist.

Still feels like a costume, though. From the time I was little, the “real me” wore jeans, She-Ra t-shirts and velcro running shoes and felt like a total badass.

[…] over at The Fat Nutritionist wrote a big ol’ post the other day about how she was not pretty as a child/young teen and then suddenly in her teens she […]

Wow, this post resonated deeply within me (also, god you’re a great writer!)

The “beauty drag”, unlocking the padlock, being tossed around by pubescent teens… incredible. I still rely on “beauty drag” but these days it’s playing with unbeautiful aspects, because I’m so gorram sick of having to continually reach for that beauty star!

In high school, I stood out for my intelligence, so I didn’t feel the need to stand out in any other way. I worked in the scene shop with power tools, so I wore t-shirts, flannels, and my trusty wingtip doc martens. A whip-thin tween, I ballooned into what felt like some sort of towering jello creature over the course of six months, and had to replace those t-shirts and flannels with… more t-shirts and flannels.

Mom dutifully took me to the mall, where to my horror, nothing in the juniors department fit 14yo me. I was 5’8″ and a size 14, which I remain to this day (I’m 29). I looked like I was in my twenties. I towered over everyone at school. I felt like I filled the space of two people. And what was in style at the time but babydoll tees. School regulations and my own dignity being bars to midriff baring, we ended up going to to Eddie Bauer instead of to the boys department, where I found the flannels and t-shirts I so desired, but the sense of being Bigger Than Everyone Else – not fatter, but bigger – and that that was a Bad and Abnormal Thing stayed with me.

I believe I’m attractive now, but my attractiveness has never been of the “cute” or “pretty” kind. The adjectives have been “elegant” and “pre-Raphealite” and “striking,” and it took a while to accept that those aren’t back-handed compliments to some chick who’s too big to be cute. I’ve got large eyes, a large nose, a wide mouth. If I didn’t have a big face to rest those on, and a big body to balance, I’d look less like this and more like this (except with a big schnozz). And trust me, you don’t want to see that second one walking toward you in real life.

Hahaha.

I also have kinda big facial features (and a big head — hats never fit me), so I hear you. I was in theatre for a long time as a kid, so my relative largeness (both in body and face) helped me project when performing, and I think they still do when I’m giving a presentation or speech or whatever.

I think I was wearing a size 10-12 when I was 14 and through high school, so I was just barely able to keep buying clothes in most “regular” stores, but I definitely looked preternaturally grown-up. I shared your experience of feeling like a GIANT, HULKING CREATURE next to my little-kid-like friends for a long time, until everyone surpassed me in height later in high school.

I literally felt like an ogre, starting around 6th grade. That feeling never entirely left me, even when people suddenly decided to like the way I looked.

Yes to all of that.

In college I discovered that I act and carry myself as though I am even LARGER than is the case. To the point where people believe I’m taller than I am. 5’8″ is tall for a girl anyway, but I’ve had 6’+ dudes express bemusement when I stand next to them for comparison. “Huh! I thought we were about the same height!” is the common refrain.

Actually, I talked to my beloved boy about it. He’s got just a couple inches on me, but one of my favorite memories is one night early in our relationship when we shared a standing hug and he looked at me (or rather, down at my forehead) surprised. “I thought you were my height! You’re little!” I protested that this was not the case, while secretly a little giddy inside, and got on my tiptoes to prove it. So he got on his tiptoes and said “Nope. Little. You’re Sid-sized.” It may not be appropriate or politic, but being told I was /little/ made me feel cute. As I said above, I have not been cute since grade school. I yearn to be cute in the way that my cute friends have told me they long to be sultry.

So earlier this week, I tell my beloved about this post and this thread, and then I told him about my own experience with feeling Big. He listened to me go over it and then gave me a hug and reminded me, “You are Sid-sized. That’s a perfect size.”

This is the most moving, most honest and most succint post I have read in the Fatosphere for a long, long time. And that is saying something because we get some pretty amazing posts on a regular basis. But THIS is something else.

You need a book deal. You need a book deal NOW.

Love your work hon.

This is a great post. I know exactly how you feel, but I approached it in a different way…I was always fat. I did have one period of time when I was in high school, when I managed to lose 90 pounds at the age of 16 and didn’t gain much of it back through the rest of high school. Then, I was just ignored (except by older men, because I had really big boobs). I know of at least two boys who really liked me, but wouldn’t go out with me or be seen with me because I wasn’t socially in their league and they would have been embarassed in front of their friends. So, I’ve been dragging that around for 30 years. I have also been married for almost 20 years to a great guy. But, in the back of my mind, I keep waiting for him to drop me. When I catch myself thinking that way….I try to block that out – that’s the old tapes playing.

Anyway, my mode of acceptance has always been about what “I do,” not how I look. I try to do a better job than anyone else, help more than anyone else, etc., etc. I have been this way since I was a little girl. I became performance-oriented because I knew, even as a young child, that there was no other way for me to be accepted and fit in at school, work or anywhere else, for that matter. My looks weren’t going to do it for me.

It was a weird combination to be rejected by my peers, yet pawed at by older men. That’s really all jumbled up in my brain. At times, I believe my weight is my “man shield.” My husband did meet me at a “skinny” moment – it was VERY brief. I probably wouldn’t be married if it wasn’t for looking good right at that moment. Then, he fell in love with me and it doesn’t matter to him what my size of the day is.

I have lost large amounts of weight a couple of times in my life….this last time was about 6 years ago. I lost 152 pounds and looked and felt great. I am not a “sexy” person. I still wear jeans, sweatshirts, comfy clothes no matter what weight I am. I worked at a baptist church at the time. I also attended the same church. My husband and I belonged to a sunday school class, where one of the married men in the group started following me around, telling me how much he loved me, holding onto my arm and not letting go, stopping by the church office to see me, etc., etc. I cannot tell you how fast my weight came back on. It was almost like I didn’t need to eat to gain it….it was back amazingly fast and it had taken me five years of diet and exercise to lose that weight. I really didn’t think I’d get fat again, but here I am. Damn.

This is a very rambling post, but my mind is in a jumble. I apologize for the lack of clarity. I’m not sure what I just typed even has anything to do with your original post…..sorry! Your post hit a nerve in me this morning. I appreciate you putting yourself out there and helping us all to know that we are never alone!

I probably wouldn’t be married if it wasn’t for looking good right at that moment.

You know, it really makes me sad that you believe this. I’m not saying you’re wrong, since you know your situation and relationship better than anyone, but what an awful thing to carry around for 20 years.

I also met my husband during my relatively brief period of passing for normal (I was always overweight by the BMI, but I didn’t start to look fat until after I got married.) I have no idea if he would have still been attracted to me if I were fat from the start, but, like yours, he definitely seems fine with me now, though I’ve gained a lot of weight since the start of our marriage. He’s also grown as a person, and I can at least take partial credit for helping him with that (he’s also helped me grow as a person in other ways, but that’s a different post for a different day.) I exposed him to the idea of fat acceptance, and I talk to him freely about eating disorders and feminism and racism and whathaveyou, and he soaks it all up like a sponge. He doesn’t always agree with me, but he is open-minded enough to listen, and he is intelligent enough to be able to incorporate new ideas into his existing frame, after he’s critically analyzed them and decides they make sense. He believes deeply in justice and, more than that, kindness — so a lot of these ideas end up making sense to him on a visceral level. Even if he wouldn’t have accepted me as fat when he was younger, I can feel happy that, mainly because of me, he no longer sees fatness as a bad thing and he refuses to judge people based on weight.

I also had the experience, when I was a kid, of getting attention from a couple of boys who obviously liked me (sending me notes in class, holding my hand under the desk, insisting I sit next to them, putting their arms around me, etc.) but who would NEVER have come out in public to say so. It was heartbreaking.

But what can I say? Kids are stupid sometimes, because, well, they’re kids. The most important thing is acceptance from the social group — that’s bred into us as primates, and not easy to shake off when you’re still an impressionable adolescent. I just don’t really hold onto any of that now, though it hurt for a long time.

I appreciate your sharing what it was like for you — for me, that’s even more interesting than the original post :)

This is a fantastic description of my own experience. I especially like your words about beauty, like class, being a construct that keeps people in a constant state of anxiety about its loss. I’ve known several people who were essentially wrecked by their own beauty, unable to grow outside the cage of their unfortunate good fortune.

One thing I think I’ve noticed is that girls of my generation (b. 1956) learned two mutually exclusive things: that you were prettier and nicer spiritually if you were ignorant of your beauty and appeal, and that your beauty and appeal were of huge importance and subject to some objective measure that determined your power and your choices.

[…] she posted a story about how her appearance changed how people interacted with her in a post called Pretty Good Looking for a Girl. There was another reason for this — when I reached puberty, but not quite fashionability, at age […]

I posted this story on our blog. http://genderequity.wordpress.com/2009/12/09/personal-experiences/

Thank you for being the inaugural post on this series, and letting us share your story. Unfortunately, I am sure that we will have a lot more :(

you know, except for the depressed part, and that it was at 17 when my padlock unlocked (and i was likened more to a bombshell due to the natural rose’ colored hair and very curvy body) this could have been written by me. i was unafraid to be unique and do my own thing and to experiment freely. i remember discovering this power and it stunned me. i remember walking the halls and hearing a group of boys teasing one of them for pining for me and being so surprised.

i am now older and fatter, but still seem to attract attention. i’m married to a man who loves me and my body, the whole package, exactly as is.

this was a wonderful read.

[…] letters to Congress, obsessing over what we’re eating on any of a number of grounds, or doing beauty drag to be vaguely socially acceptable–people need to feel like we have some kind of control over […]

Wow. This was written beautifully and thoughtfully. It spoke volumes to me. Chasing beauty, imagining it would make the world so much better. Then becoming that beauty and being confused when good looking people want to hang out with you.

I’m very glad you have this blog in general, its encouraging and inspiring.

Thanks.

I’m de-lurking to say that this post deeply resonated with me. I’ve been a heavy person all my life, roughly excepting my four years of high school, when I remember that feeling of the padlock suddenly opening really distinctly. To this day I struggle with processing that experience, and still mourn a lot of the access I had to the privileges of beauty, even knowing that I’m a healthier person now.

Basically, the turning point came when I developed a pretty serious case of bulimia. I’m 5′ 3″, and I went from 120 pounds – hardly a giantess in any sense – to 90 in the course of a month, and then did everything humanly possible to stay in the double digits. It was, in retrospect, a totally humiliating and degrading process to inflict on myself. I wouldn’t wish it on anyone I know or care about. Like you, I met my long-term partner while I was thinner and he probably wouldn’t have dated me if he’d met me at my current weight (169); like in your case, he clearly doesn’t mind the weight gain and values the relationship on a level that I never thought I would experience personally. I am very lucky.

And yet I remember the intoxication of walking into a room and immediately knowing on a visceral, gut level that I could command the attention of everyone there, and it was an insipid, indulgent thing to gain pleasure from to be sure, but I miss it still.

I mean, having said that, for the most part I don’t care that I’ve gained weight. I’m happier now, and much, much, much healthier, and live my life in a much more fulfilling and rewarding way. But every now and then – like when I develop a crush on someone and realize that, at my former weight, it would definitely have gone somewhere but that I’m now completely undesirable as a cultural object of beauty – the knowledge of what I’ve lost stings. I’m still struggling to get to the relief. All my ardent feminist beliefs and ideology quail in the face of knowing what I used to have – and maybe that’s the most insidious thing about the societal construct of beauty.

Phew, sorry to go on so long. I could have said all that in a sentence: long-time reader, coming out of the ether to say that this post from over a month ago really struck a chord with me, thank you.

Beauty is so weird. I have a symmetrical, long oval face with well defined features. And I have a tall wide shouldered figure that holds good proportions through a range of weights. I LOVE my face. I SHOULD be beautiful. I look at myself in the mirror and almost always think (at 41) that I’m pretty cool-looking and blessed, overall. But I am not a conventional dresser, I am not good at putting or keeping makeup on my face, and I photograph badly. I am not femme. So I have always been lumped in with the unpretty in how society responds to me, even though I am personally quite happy with how I look.

I think I stopped caring when I was about 30. That doesn’t mean that I don’t take care of myself, dress nicely (what I think is nicely) or try to manage my weight. But I am just never going to be able to put on that feminine disguise. I started to realize that being fat in my 20s helped make people take me seriously when I was in grad school; but then my face being well-shaped probably helped keep it from being too much of a negative. Lately I’ve taken off a bunch of weight but it doesn’t really seem to matter, I have never been able to find the disguise.

[…] has been going crazy about weight, beauty and the perception of weight and beauty lately. Do read The Fat Nutritionist (English), Health at every size (Swedish) and Julia Skott (Swedish) … and then check out […]